How Africa United to Protect Its People Against COVID-19

“Public health in Africa has been a story of neglect and dependency,” says Dr. John Nkengasong, the first director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control, in an interview with the New York Times about how they’ve has responded to COVID-19 in Africa. When the Africa CDC was created in 2017, it aimed to “help Africa speak with a unified voice”, and create a centrally-located place for governments all over the continent to respond effectively to public health threats, without having to rely on other organizations like the World Health Organization. While Ebola could have been a much more devastating virus for Africa, there was a sense that it was a sign that something worse was possible.

New information emerges daily and the COVID-19 landscape continues to change rapidly, but we’ve done our best to give you an overview of Africa’s current COVID-19 status, response efforts, and ongoing challenges on the continent.

THE CURRENT STATUS OF COVID-19 IN AFRICA

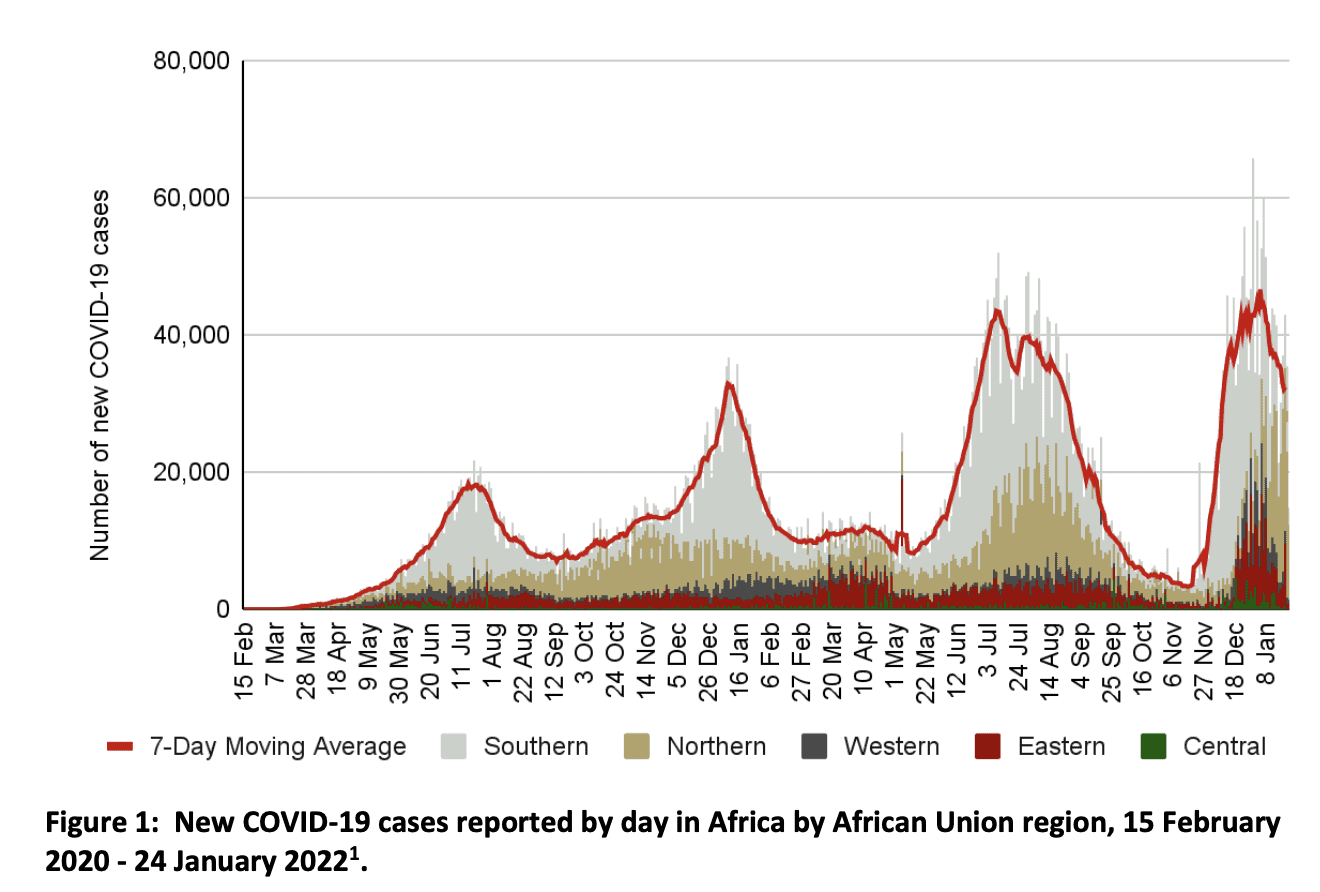

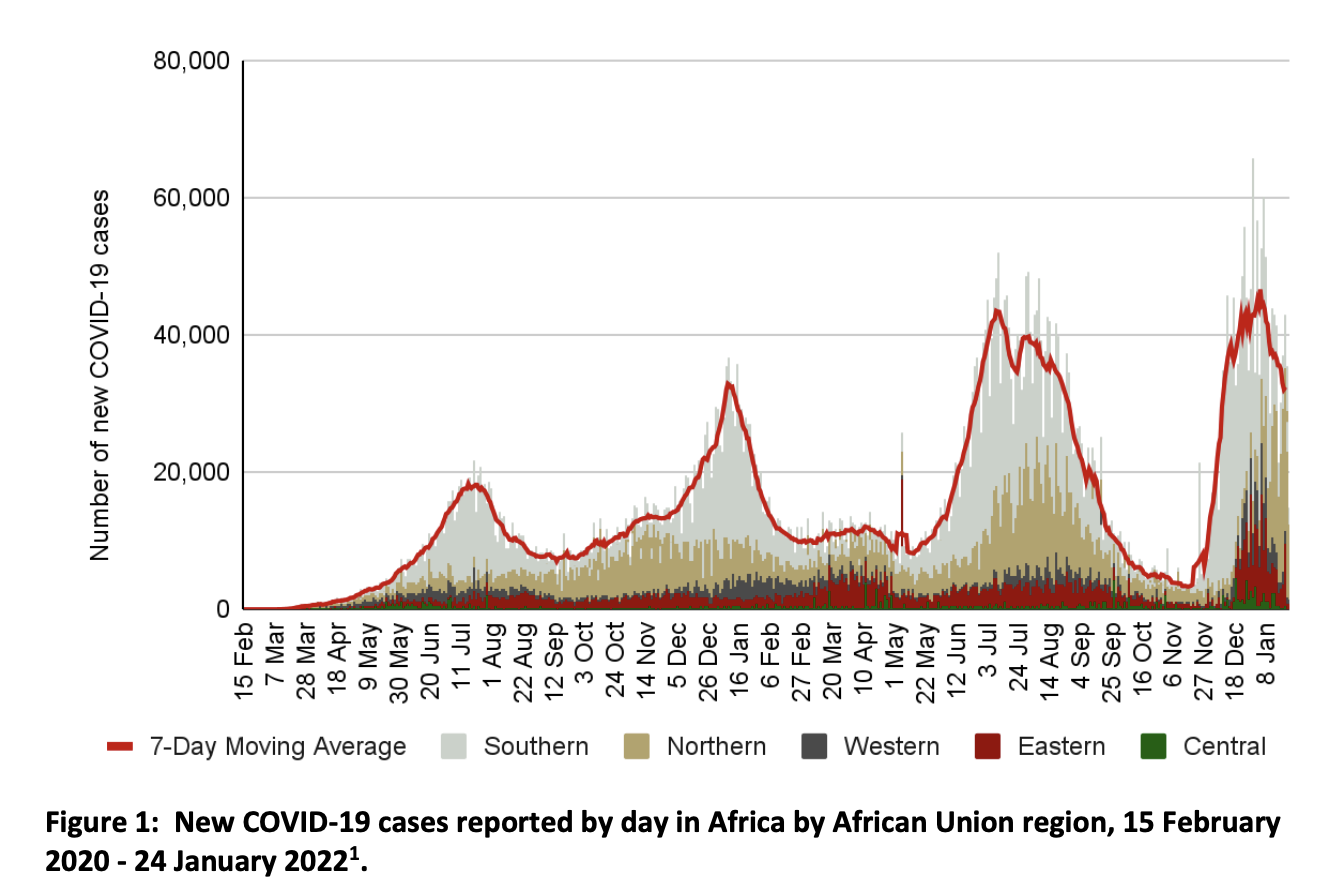

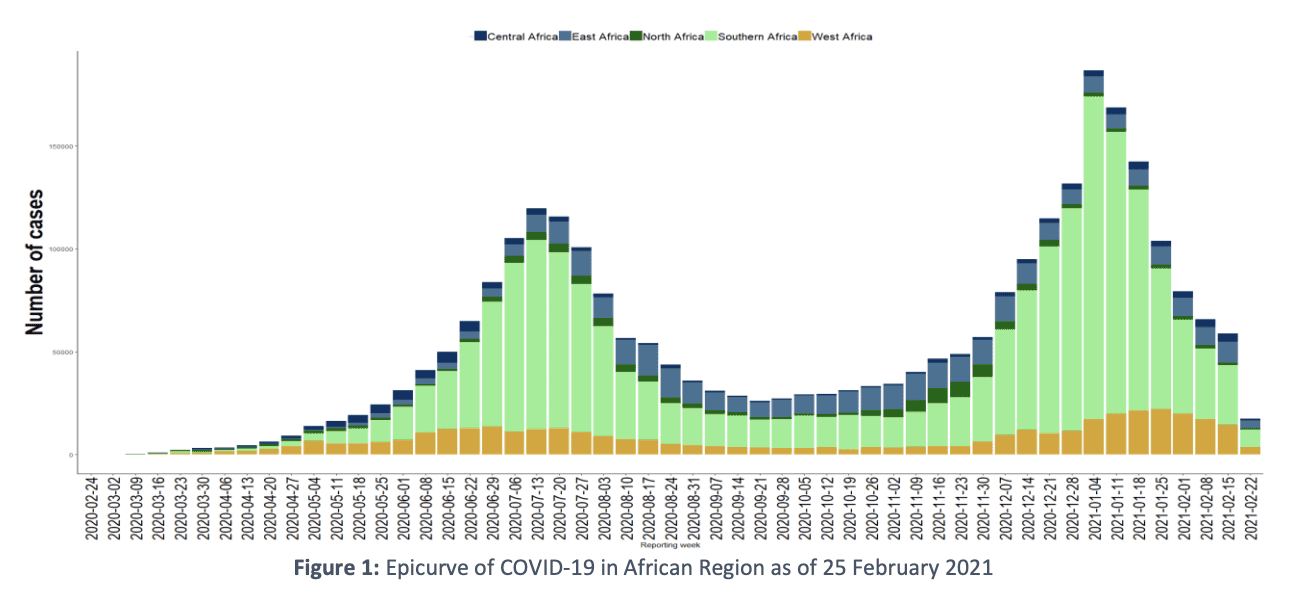

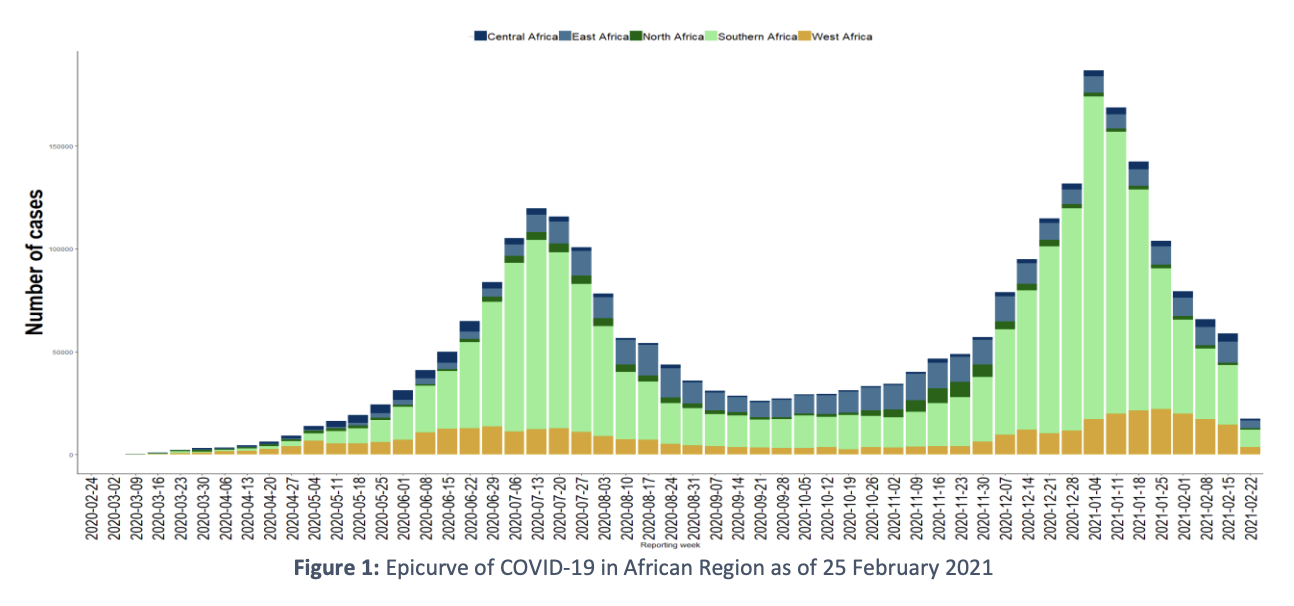

According to the Africa CDC and African Union, as of January 24, Africa has had 10,591,594 COVID-19 cases, 3% of all the cases in the world. Looking in terms of the WHO African Region bulletin, South Africa has had the highest number of cases, followed by Ethiopia (457,322), Kenya (317,634), Zambia, and Nigeria, accounting for 64% of all cases in the region. Since the beginning of the pandemic, 53 of the 55 members of the African Union have experienced a 3rd wave of the virus, 46 (84%) have experienced a 4th, and 8 (including Kenya where 3 of our partners operate) are experiencing a 5th. Over 94 million tests for COVID-19 have been conducted since February 2020; the cumulative positivity rate being 11.3%.

Africa has also experienced 237,007 deaths, 4.2% of all deaths globally (Africa CDC). South Africa has also had the most reported deaths in the region with 58% of the number, followed by Ethiopia (7,147) followed by Algeria, Kenya (5,488) and Zimbabwe, together accounting for 74% of the region. As of January 16, there have also been 6.8 million recoveries, a recovery rate of 90%. (WHO bulletin).

The average case fatality ratio (CFR)—the proportion of deaths per confirmed cases—is 2.2% for the 55 African Union Member States, 28 of whom report higher CFRs than the global ratio (Africa CDC). There have been 150,387 COVID-19 infections among health workers in the WHO African region; notably in South Africa at 48% of them, Algeria, Kenya (7%), Zimbabwe. Only Eritrea has not reported any (WHO bulletin).

Declining Trends

For the last month, cases and deaths in the region have been falling in a majority of countries, following a five-week rise in new cases (WHO bulletin). Luckily, this was the shortest spike yet, at 56 days, and only North Africa has seen an increase in cases recently (WHO). More than half of the new cases reported the week of the 16th, were in five countries: South Africa; Zambia; Ethiopia (13,198 new cases, 24.4% decrease, 11.1 new cases per 100,000); Mozambique; and Kenya (6,276 new cases, 51.2% decrease, 11.1 new cases per 100,000).

The number of new deaths reported fell by 215% that same week (WHO bulletin), a dip for the first time since the peak of the 4th pandemic wave propelled by the Omicron variant. This wave had the lowest cumulative average case fatality ratio to date in Africa: 0.68% vs the 3 previous waves which were above 2.4%. This ratio continues to be the highest in the world. The Regional Director of the WHO for Africa, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti remarked, “While the acceleration, peak and decline of this wave have been unmatched, its impact has been moderate, and Africa is emerging with fewer deaths and lower hospitalizations. But the continent has yet to turn the tables on this pandemic,” (WHO).

For the 3rd week of the month (January 17-23, 2022), 1,380,216 new tests were conducted, and 224,648 new COVID-19 cases were reported, a 13% decrease compared to week 2. There were 2,290 deaths, a 19% decrease (Africa CDC).

The Africa CDC releases a weekly outbreak brief, biweekly briefs on the latest developments in science and public health policy around the world, and updates on the latest guidance for African nations. To see the most recent COVID data, you can see the Africa CDC’s Dashboard and COVID site, and the WHO African Region’s COVID page and dashboard.

THE INTERNATIONAL PLAN TO FIGHT COVID-19

Existing Challenges

There were already a large number of insecurities that many countries’ health infrastructures faced, which have just been overwhelmed with surges of COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa. The 2021 COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan (SPRP) was created to guide countries from February 1, 2021-January 31, 2022 to holistically respond to COVID-19 at regional, national and sub-national levels, while maintaining other health needs outside of COVID-19.

While a number of countries did have strong and quick responses to the pandemic, and all countries created quick response plans, these have often become less structured and followed since, especially in fragile settings. Supplying necessary tools for treating COVID-19 and severe cases has become much better, though still not enough, and often affected by shutdowns and restrictions, even in countries that were more prepared. There also continues to be a worldwide challenge getting supplies where needed, shipping taking longer than normal, and less products and supplies available in general.

Since the pandemic has had a slower spread than in many other regions, it’s helped the world understand factors that cause faster spread elsewhere and help plan for Africa. In Africa, most people who have contracted the virus are younger with no comorbidities, so the majority have not needed large intensive interventions. However when patients do become seriously ill, they often need weeks on a ventilator, which is much harder to come by in the region.

The shortage of health workers, poorer health infrastructure, inadequate medical supplies and so on, meant that there were already not enough resources and COVID-19 has just exacerbated these weaknesses. More infection of healthcare workers may be because of lower awareness of the virus, inadequate PPE (which travel restrictions also affect), and lack of testing. There is a higher overall instance of chronic conditions and a high level of poverty, which both contribute to more severe COVID-19.

Since many places have a stronger cultural emphasis on community, this can be used to help with public health measures, and has to be taken into consideration when planning outbreak response, rural and urban. Testing has grown a lot as well, from 2 national laboratories to nearly 1,000, as has availability of rapid antigen tests. Continued challenges are the time it takes to return test results, and the insufficient number of testing kits.

The 11 Pillars of the Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan

1 – Coordination, planning, financing, and monitoring

Multisector coordination at global, regional, national, and subnational levels ensures effective pandemic preparedness, response, and recovery and maximizes available resources, focusing on vulnerable communities and local contexts. Reviewing plans also helps make sure concurrent health concerns can continue to be addressed and that resources will be managed if there is another surge of COVID-19 in Africa.

2 – Risk communication, community engagement, and infodemic management

Negative impacts of COVID-19 on individuals and communities will be reduced using evidence-based, people-centered, community-led approaches. Disbursing timely, credible, relevant information helps manage the infodemic (an overabundance of information, including misinformation). These approaches mean more people will willingly follow public health measures, the most powerful means to stop the spread.

3 – Surveillance, outbreak investigation, and calibration of public health and social measures

People suspected of having COVID-19 should be rapidly tested and cared for, as should their contacts. Communities must figure out where the virus has spread, transmission intensity, disease trends, and impact on health-care services, then calibrate what sorts of health measures are necessary. Where large scale testing is limited, mortality and respiratory diseases should be monitored, with early detection through clusters and health workers. All measures should be regularly reviewed and effectively communicated with affected communities.

4 – Points of entry, international travel and transport, and mass gatherings

International travel and transport measures should be informed by risk assessment, local epidemiology, travel volumes, and health service capacities in the travelers’ destinations and origins. These may include advice to travelers, disease control, case management, and international contact tracing. Testing resources should never be diverted from high-risk groups.

5 – Laboratories and diagnostics

Extensive, systematic testing/sequencing, and data sharing and analysis prevents the spread of COVID-19 in Africa through rapid identification of infected individuals, new viral variants which may affect transmissibility or severity of infection, resurgences, changes, and impact on public health measures. Countries should manage testing at national and sub-national levels, while building on this capacity for other relevant diseases.

The WHO, alongside the Africa CDC, launched the Africa Regional Sequencing Laboratory Network for COVID-19 and other emerging pathogens. This is a system of 3 Specialized and 9 Regional Reference labs that can perform genome sequencing and analyze data for all African countries. However, more labs and better sequencing is very important to ensure timely access for everyone. The Institute of Pathogen Genomics is part of the Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative that started in 2019, which aims to support these capabilities across the continent and maximize tools, training, and coordination, for decision-making and responding to all disease threats.

6 – Infection prevention and control (IPC) and protection of the health workforce

Health facilities and communities need to identify and manage patients infected with COVID-19, and prevent transmission or any increase in mortality for any health issue. The community must be aware of public health preventive measures, and there must be alternatives if there is a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). All of these measures also depend on access to safely managed water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), particularly for vulnerable communities.

7 – Case management, clinical operations, and therapeutics

Health service delivery networks should be ready for large surges in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 at local, sub-national and national levels.

8 – Operational support and logistics, and supply chains

Countries must be able to manage incidents and expedite necessary functions like procuring essential supplies. The COVID-19 supply chain system needs to provide these equitably between all health care providers and where needed most.

9 – Strengthening essential health services and systems

When health systems are overwhelmed, they still need to minimize mortalities and maximize all essential health services, while balancing the direct response to COVID-19 in Africa. They need to regularly monitor how well they can provide health services to decide on the future, still considering the local context and vulnerable populations. High priorities include preventing and treating communicable diseases (malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, etc), averting maternal and child morbidity and mortality, exacerbations of chronic conditions, critical inpatient therapies, and time-sensitive emergency conditions.

10 – Vaccination

Countries need to be prepared for deployment of vaccines through planning, regulation, communication, training, infrastructure, and so on to successfully distribute them in a timely and efficient manner. Mass campaigns can be challenging in fragile settings.

11 – Research, innovation and evidence

Countries are encouraged to use standardized protocols and quality, evidence-based knowledge to decide how they want to plan and respond to all of these concerns.

For reference, the Africa CDC’s current recommendations for African Union Member States are as follows:

-

Enhance COVID-19 surveillance efforts to include influenza-like illness (ILI) and severe acute respiratory infections (SARI), mortality data, presence of variants, spread and continuous evolution of the virus, and symptomatic cases for early treatment and to avert viral transmission

-

Perform contact tracing of confirmed cases and enhance diagnostic screening efforts using the rapid antigen tests

-

Notify and routinely share data with both the WHO and the Africa CDC regarding confirmed COVID-19 cases, deaths, recoveries, tests conducted and infected healthcare workers for updated information for action

-

Guide the general public about seeking immediate medical care for those who develop severe symptoms

-

Place or strengthen existing public health and social measures if COVID-19 incidence starts to rise

RESPONDING TO THE PANDEMIC IN AFRICA

In the aforementioned interview, Dr. Nkengasong explains the state of COVID in Africa, “An emergency is where your house is on fire. You run around, you call 911, they come sprinkle water. That phase is over. We are now in a phase where your house is burned down. How to build a new house? … I think this virus is winning. As a continent, we are not winning. Today we have more than seven million cases with close to 180,000 deaths. And the death rates are all increasing very dramatically across the continent… It still has to be a battle that is won or lost at the community level. Misinformation continues to be a serious issue.”

The WHO maintains that vaccination, social distancing, avoiding poorly ventilated or crowded spaces, hand-washing, and well-fitting masks are the important steps people can take to reduce the spread of COVID-19 (WHO bulletin). Many African countries still have major challenges treating COVID-19 between the availability and costs of solutions. There may be more oral antivirals and drugs that will reduce risk of hospitalizations and help treat people with severe cases.

There have been improvements in the number of ICU beds for COVID-19 patients from 0.8 per 100,000 people to 2, but a lot more are needed to meet needs. Corticosteroids needed to treat severe cases are pretty much available and affordable, but medical oxygen continues to be elusive for much of the continent (WHO). Dr. Nkengasong also remarked upon Africa’s small number of health workers and the fact that Africa’s health plan was designed around having a population of less than 300 million, which has grown to 1.2 billion, and will be around 2.4 billion in the next 30 years.

Though those interventions are extremely important, experts and leaders in the response maintain that ramping up vaccinations on the continent is integral to seeing any sort of end to this virus, especially considering the impact of new variants. “So long as the virus continues to circulate, further pandemic waves are inevitable. Africa must not only broaden vaccinations, but also gain increased and equitable access to critical COVID-19 therapeutics to save lives and effectively combat this pandemic,” Dr Moeti stated (WHO).

While there is an increasing number of vaccine supplies going to Africa (570 million supplied), just 10% of the continent’s population is fully vaccinated, and 15% is partially vaccinated, with 353.1 million vaccines administered. In 2022, an expected average of 250 million to 300 million doses of vaccine will be available for supply each month, and by the middle of the year, significant efforts will be necessary to reach large portions of the population (WHO).

Dr. Nkengasong also claims, “No people will survive with importing 99% of their vaccines and importing 100% of their diagnostics. It doesn’t make sense. We need 6,000 epidemiologists. We currently have only about 1,900 on the continent… However, when I look at the trends, what is happening on the continent, I’m very encouraged.”

Here is the Africa CDC’s vaccination dashboard, and a link to PERC, the Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19, to help members of the African Union get the information they need to make decisions on COVID response. For more info about the continent’s response, you can see Dr. Nkengasong’s update on COVID-19 in Africa from January 20, which you can see on their Facebook Page.

Our Partners’ Response

Blood:Water partners with African-led organizations serving their local communities, and our partners’ ongoing health work is directly related to the COVID-19 crisis. As our world has battled this new virus, our partners remain on the frontlines, leading their community response, and serving with compassion.

Since the beginning of the global spread, our partners have been hard at work, ensuring adaptability and preparedness among their teams and communities. Many have emerged as leaders at the national level in their countries’ response to the pandemic. Before the first cases of the coronavirus emerged on the African continent, our partners were already pivoting their services and mobilizing teams to educate communities on the virus and how to prevent it.

To see more about how our partners have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa and how the pandemic has affected their work in and those afflicted by HIV/AIDS, stay tuned for part 2 of this blog.

More Stories:

Categories