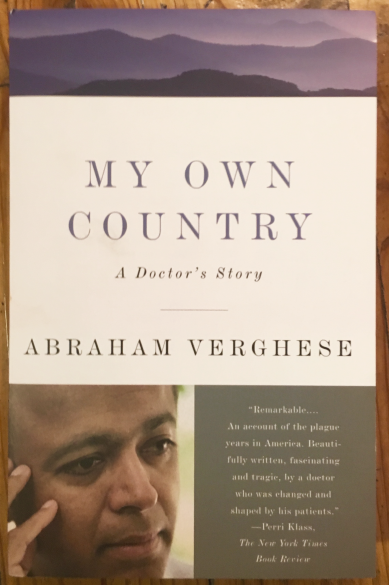

Today we will review chapters 1-5 of “My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story” by Abraham Verghese.

Summary:

Section one of “My Own Country” introduces the fascinating story of Abraham Verghese. An immigrant of Indian descent from Ethiopia, Verghese is trying his best to integrate into the rural town of Johnson City, Tenn., in the 1980s. The book begins with a very interesting and attention-grabbing medical mystery. The reader knows the patient is an HIV-positive man who will soon decline and pass away from pneumonia, but for the emergency room team in Johnson City, it is a medical anomaly. We are also introduced in the first chapters of the book to the extreme stigma that falls upon HIV-positive patients, specifically within the realm of the gay community, which was nonexistent in rural Tennessee at that time. Verghese quickly became aware of the fear, shame, and lack of compassion HIV-positive patients experienced, not only from family members, but from the doctors as well.

This section provides a detailed first glance into Verghese’s early life, education, and family. Readers are also introduced to the harsh reality of stigma surrounding the inception of the AIDS epidemic in the United States in the 1980s.

Themes:

Stigma, Community

Powerful Lines:

- “This was a small town in the country, a town of clean-living, good country people. AIDS was clearly a big city problem. It was something that happened in other kinds of lives.” (13)

- “There seemed no reason to believe that when AIDS arrived on the scene that we would not transfix it with our divining needles, lyse it with our potions, swallow it and digest it in the great vats of eighties technology.” (25)

- “The metaphor of AIDS is so powerful, it seems impossible to eradicate the term.” (30)

- “In retrospect, when I entered a clinic room to see a gay patient, I seemed to have been carrying a shield to protect myself and I cautiously operated from behind this shield.” (58)

- “The town was aware of homosexuals and AIDS, but by God, the less one thought about or discussed these things, the better.” (72)

- “I have grown to realize through years of treating gay men how few of their families were able to see their sons’ best, most engaging selves.” (92)

- “They could not bring themselves to see what was now plain to me: Gordon was very sick. And I could not begin to help Gordon as long as he insisted he was all right. It was almost a relief when he finally told me. I used to wake up and thank God for bringing him back and then worry exactly what it was he had come back with.” (100)

Questions to Ponder:

- Is there an excuse for the nurses and doctors who didn’t want to treat AIDS patients or for the family members who were so fearful of the disease they wouldn’t visit the bedside of their loved ones?

- Should people who have committed themselves to careers as doctors or nurses be morally obligated to treat any and every patient?